The Kyshtym Nuclear Disaster: A Soviet Secret

The Kyshtym Nuclear Disaster, sometimes referred to as the Mayak Disaster or Ozyorsk Disaster, was a level 6 nuclear accident on the International Nuclear Event Scale (INES).

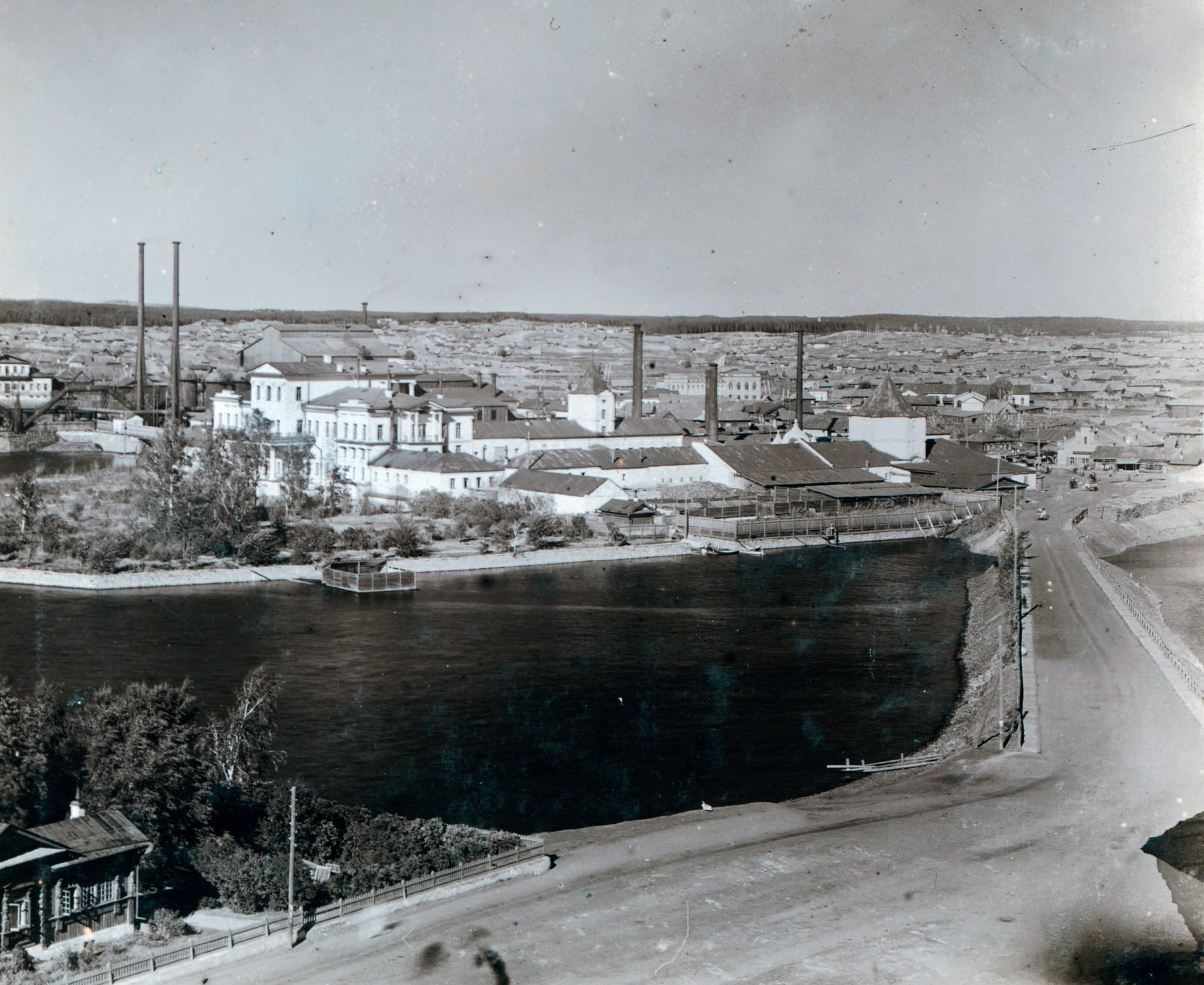

The disaster involved an explosion of radioactive waste at the Mayak plutonium plant in the closed city of Chelyabinsk-40 (now Ozyorsk) in the Soviet Union on September 29, 1957.

The Kyshtym disaster ranks as the second-worst nuclear accident by radioactivity released, after the Chernobyl disaster. However, Soviet officials concealed the disaster for three decades.

The Soviet Nuclear Program: A Race Against Time

After World War II, the Soviet Union lagged behind the United States in developing nuclear weapons. To catch up, the Soviet government began a hurried research and development program to produce a sufficient amount of weapons-grade uranium and plutonium.

The Mayak plant was hastily built between 1945 and 1948, with environmental concerns taking a backseat during this early development stage.

Mayak: A History of Neglect and Accidents

From its inception, the Mayak plant exhibited a disregard for safety and responsible waste disposal. High-level radioactive waste was initially dumped into a nearby river that flowed into the Ob River and eventually reached the Arctic Ocean.

The plant's six reactors, situated on Lake Kyzyltash, employed an open-cycle cooling system that discharged contaminated water back into the lake.

As Lake Kyzyltash quickly became contaminated, the Soviets used Lake Karachay for open-air storage of radioactive waste. This decision soon made Lake Karachay one of the most polluted places on Earth.

Mayak's operations led to several fatal accidents. In 1953, a worker developed severe radiation sickness, requiring amputation of both legs, highlighting the plant's lack of safety precautions.

The Kyshtym Disaster: A Preventable Catastrophe

The Kyshtym disaster stemmed from the failure to repair a malfunctioning cooling system in a buried tank storing liquid reactor waste.

The tank's contents, heated by radioactive decay, reached a temperature of about 660 °F (350 °C) on September 29, 1957. The tank exploded with a force comparable to at least 70 tons of TNT.

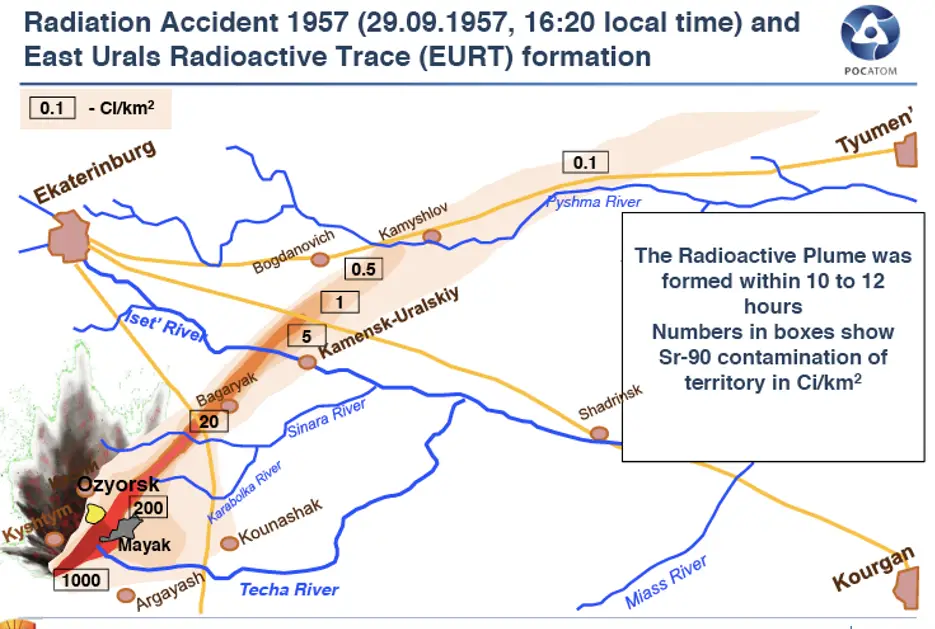

While there were no immediate deaths from the explosion, the blast propelled a plume of radioactive fallout, including significant quantities of long-lasting cesium-137 and strontium-90, into the air. This plume contaminated thousands of square kilometers of land, an area now known as the Eastern Ural Radioactive Trace (EURT).

A Veil of Secrecy

Despite the disaster's magnitude, Soviet authorities enforced a strict information blackout.

Even the populations of affected areas remained unaware of the incident. Although vague reports of a "catastrophic accident" surfaced in Western media, Soviet officials systematically denied them.

The Truth Emerges

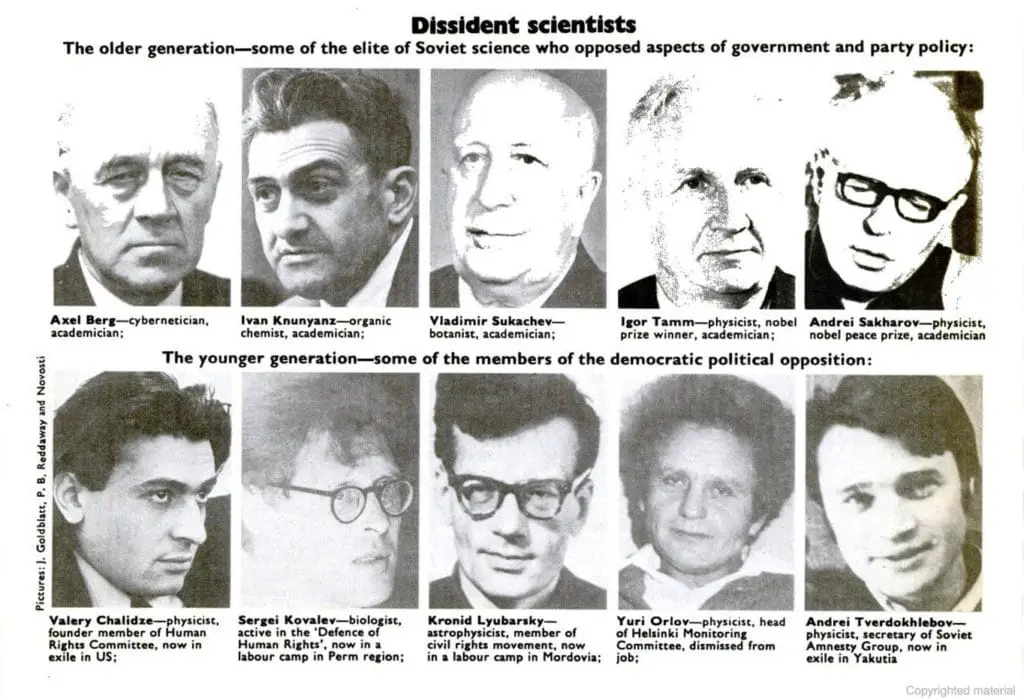

The Kyshtym disaster remained largely hidden until 1976 when exiled Soviet biologist Zhores Medvedev exposed the incident in the British journal New Scientist.

Lev Tumerman, a Soviet scientist who later emigrated to Israel, corroborated Medvedev's claims with his own account of traveling through a desolate, contaminated zone.

Consequences and Legacy

The Kyshtym disaster resulted in the evacuation of 10,000 people from the affected areas. At least 22 villages suffered radiation exposure, and the disaster's long-term effects remain challenging to assess fully.

Residents of the region have reported increased rates of cancer, deformities, and other health issues. The incident serves as a stark reminder of the devastating consequences of nuclear accidents and the importance of transparency and accountability.

The Kyshtym disaster in the Context of the Cold War

The Kyshtym disaster unfolded during a period of intense secrecy and mistrust between the Soviet Union and the West. The Soviet government's suppression of information about the event highlights the political climate of the Cold War.

Adding to the intrigue, the CIA knew about the Kyshtym disaster as early as 1960 but kept it secret. Some experts suggest the U.S. government remained silent to avoid raising concerns about the safety of their own nuclear program.

This complex interplay of events underscores the profound influence of the Cold War on the perception and handling of nuclear accidents.